The Bibliothèque Humaniste is home to 154 medieval manuscripts and 1,611 early printed works from the 15th and 16th centuries.

Learn more about some of these rare treasures.

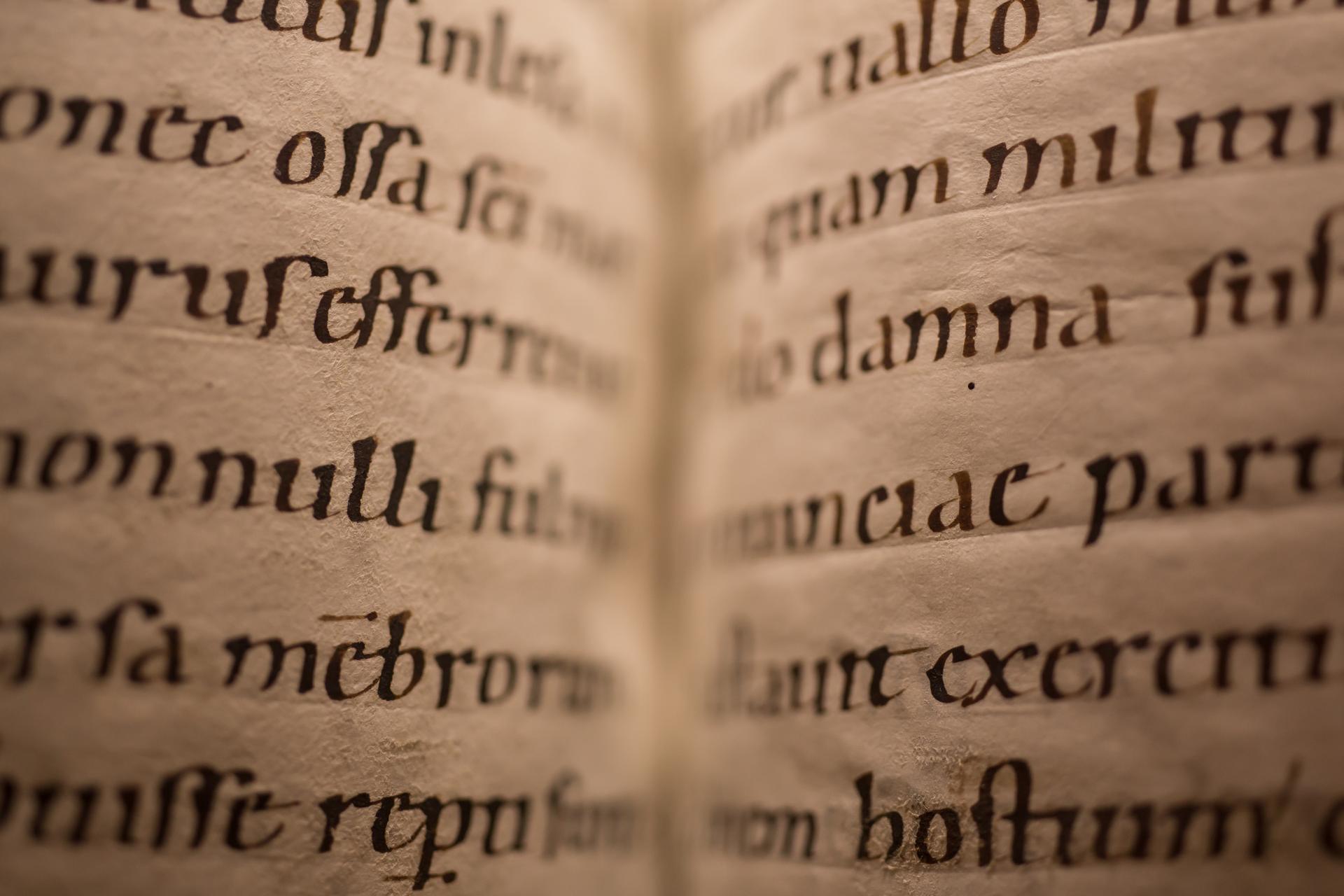

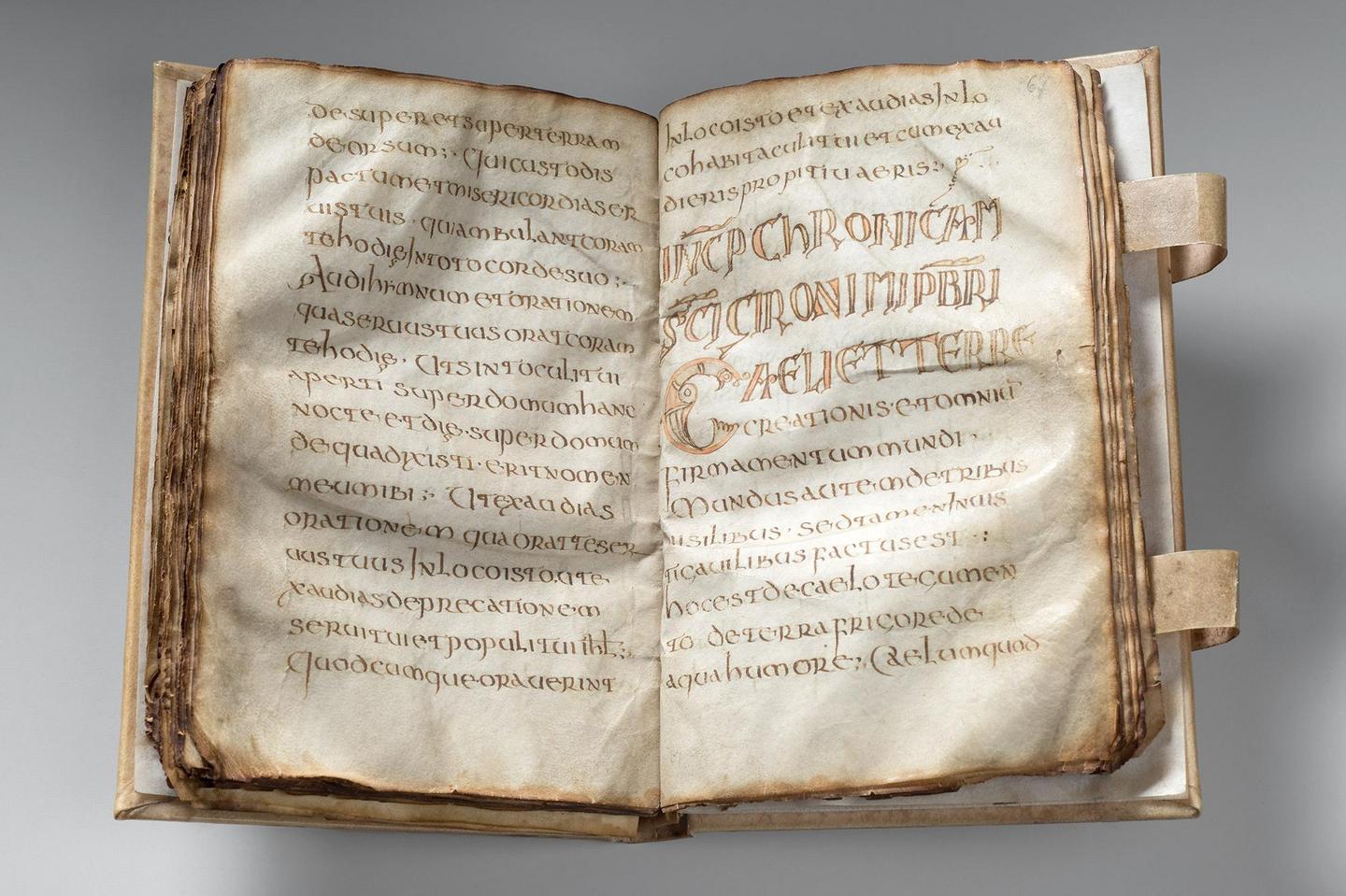

This manuscript is the oldest book preserved in Alsace. It was hand crafted in Northern Italy.

The Merovingian Lectionary begins with a liturgical anthology containing texts to be read during religious ceremonies. The second section of the manuscript is a Universal Chronicle, an account of the history of the world in chronological order. The original text is attributed to Saint Jerome.

The Book of miracles of Sainte Foy is a religious manuscript, illustrated with around a hundred illuminations featuring plant motifs, human figures and fantastic beasts. Among other material this volume contains the most complete surviving collection of the miracles of Sainte Foy, along with the legend of the foundation of the Benedictine priory in Sélestat.

This is one of the museum’s finest manuscripts.

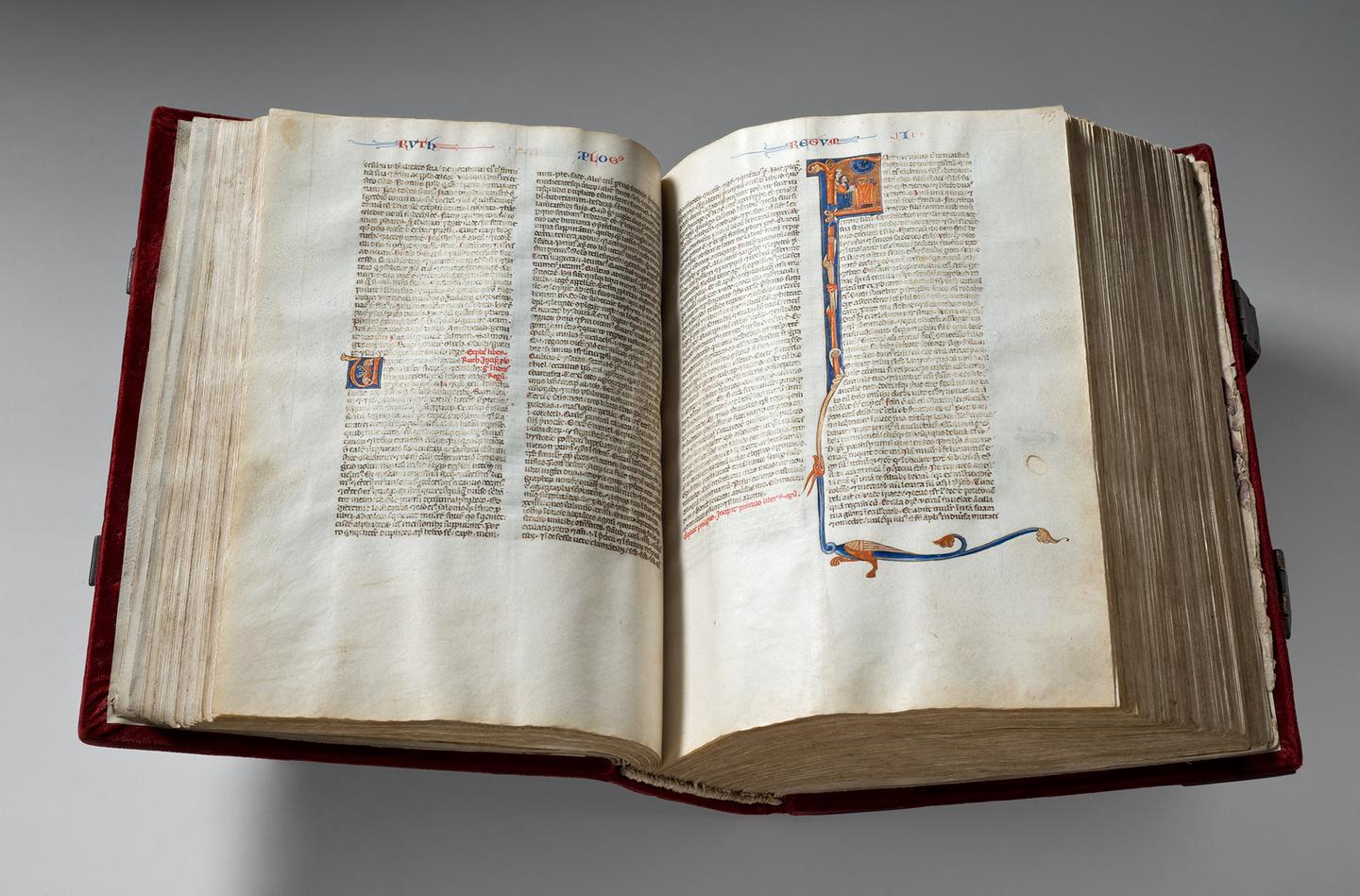

This Holy Bible was given to the parish of Sélestat in January 1573.

This volume contains the Vulgate text, a Latin translation of the Bible completed in the late 4th century. It features numerous illuminated panels. Some of them are adorned with gold and a blue pigment derived from the semi-precious stone lapis lazuli. The layout and style of the manuscript are typical of Parisian bibles of this period. According to a handwritten note in the back of the volume, it was purchased in Constantinople.

Since 1694, this precious volume has been protected by an oak case designed to mimic the appearance of a book binding.

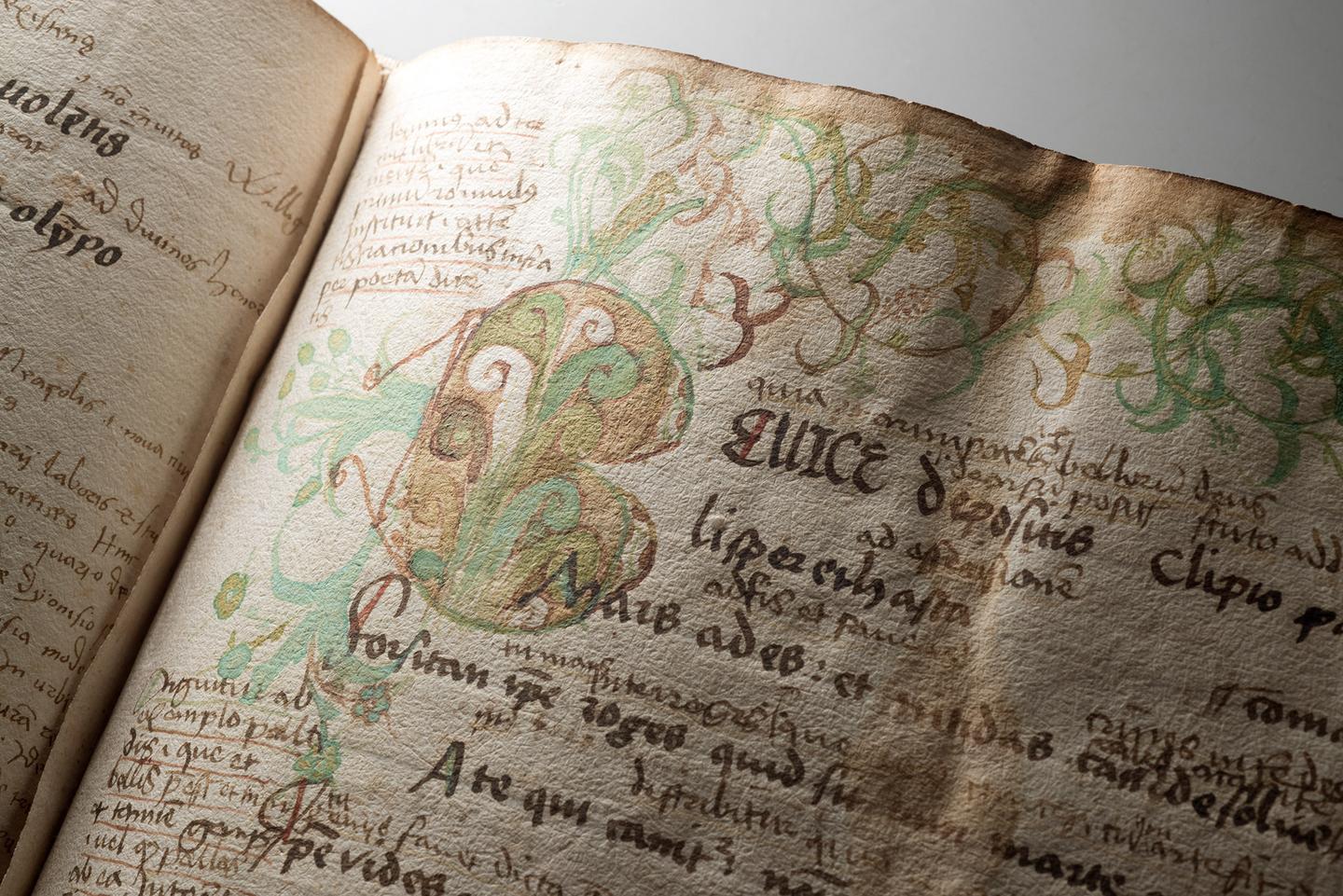

Written over five centuries ago, this Renaissance-era school notebook is a very rare historical document.

Beatus was around thirteen years old when he wrote out these lines, taking dictation from schoolmaster Crato Hofmann. Hofmann taught at the Sélestat Latin School from 1477 to 1501, taking up the mantle of Ludwig Dringenberg, who introduced a number of innovative teaching methods.

This workbook bears the traces of these innovations, but also reflects the educational priorities of Crato Hofmann: combining moral and religious education, with close study of Latin texts from ancient and contemporary authors.

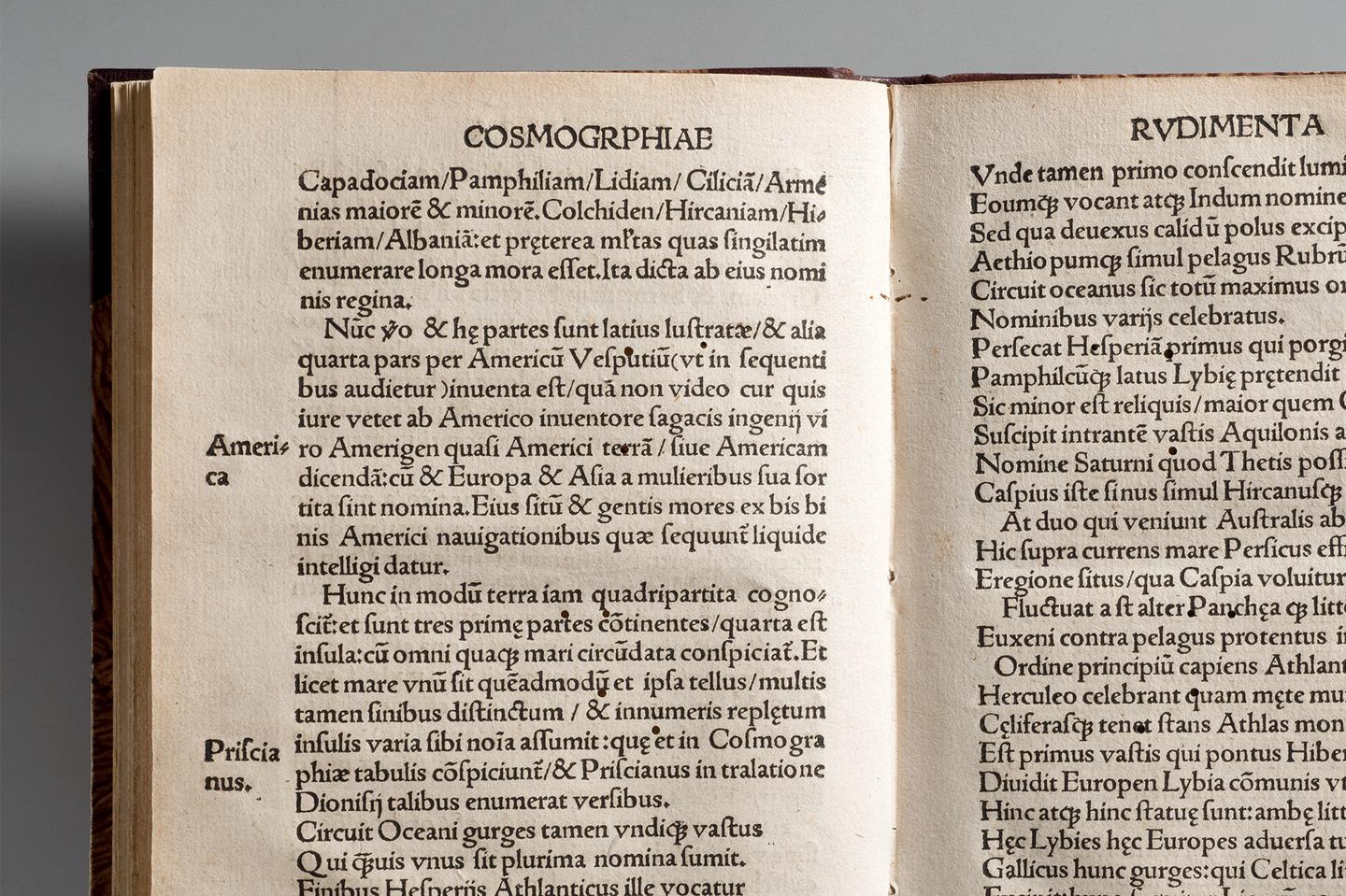

This geographical work was associated with the updated edition of Ptolemy’s Cosmographia, an ancient text rediscovered in the 15th century.

Establishing this new critical edition was a daunting task, and authors Matthias Ringmann and Martin Waldseemüller decided to begin by publishing an introduction to Ptolemy’s work which would serve to whet the appetites of future readers.

This text is often considered to be “America’s birth certificate,” as it is the first work to refer to the recently-discovered continent by the name of explorer Amerigo Vespucci. An account of his four voyages of exploration is included in this volume.

Only a handful of copies of this first edition have survived. It was this seminal text which helped to establish “America” as the generally-accepted name for the New World among 16th-century geographers.

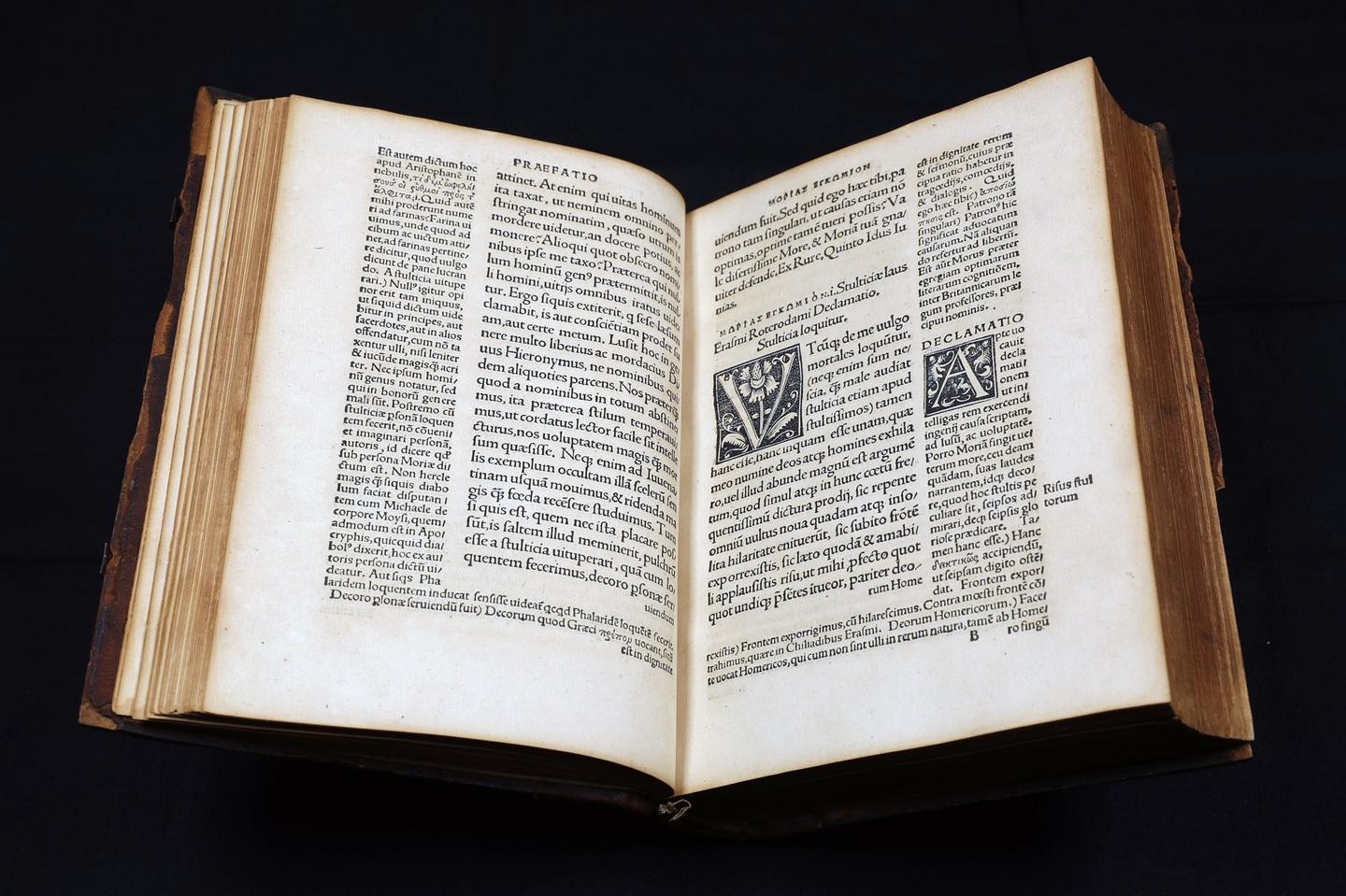

One of the most celebrated works by emblematic Dutch humanist philosopher Erasmus of Rotterdam, In Praise of Folly is a work of social, moral and political criticism denouncing abuses committed by the clergy, as well as the excesses of mankind in general.

Written in July 1509, upon Erasmus’ return from a trip to Italy, it was first printed in Paris in 1511. This edition proved to be a great success, much to the surprise of its author and in spite of the virulent criticism it received from the very theologians whom Erasmus lampoons in the text.

The original Greek title, Moriae Encomium, was a chance for Erasmus to make a punning reference to his friend Thomas More, to whom the book is dedicated.

The sermons written by Johann Geiler on the subject of Lent – the period of abstinence observed in the forty days before Easter – are here gathered together in an edition compiled by his secretary Jakob Other in 1510.

The text denounces contemporary moral failings, and takes inspiration (while also borrowing its title) from the Ship of Fools, a famous work by Geiler’s friend Sebastian Brant.

Geiler’s sermons are illustrated with 113 woodcuts, also used in the original edition of Brant’s Ship of Fools.

Geiler was a hugely popular preacher at Strasbourg Cathedral from 1478 until his death in 1510. Preaching his sermons in German, Geiler aimed to steer Christians back to the path of righteousness which leads to Salvation. This collection, published shortly after Geiler’s death, also contains the first biography of the preacher, written by none other than Beatus Rhenanus.

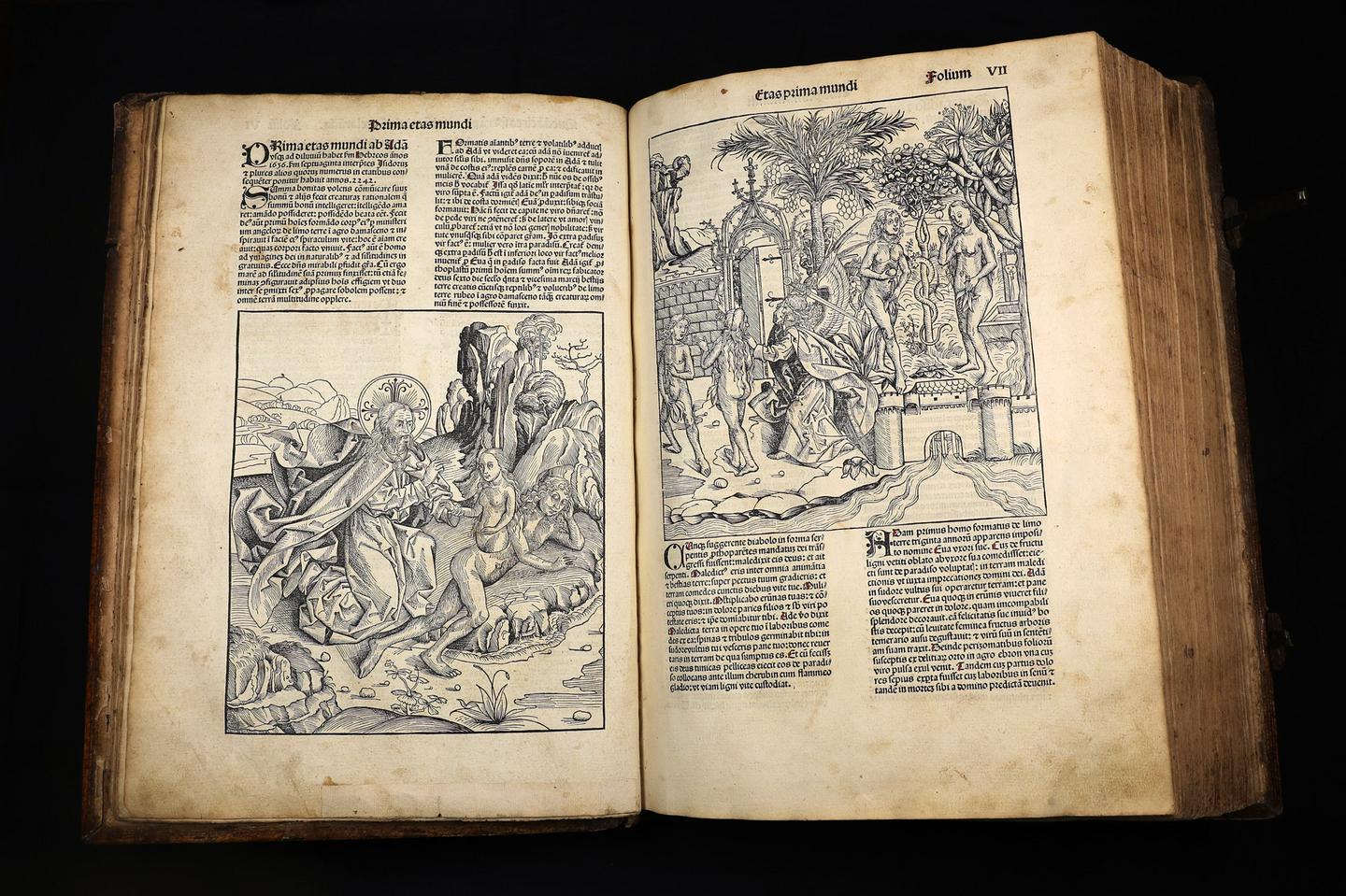

Throughout the Middle Ages, chronicles were a prime source of historical, religious and worldly knowledge designed to help readers make sense of the world. With the advent of the printing press and woodcut images, it suddenly became possible to print large numbers of copies complete with illustrations. The

Liber Chronicarum is a fine example of this tradition, containing some 1800 woodcut engravings. The success of this work owed much to its numerous panoramic illustrations, including views of cities such as Strasbourg.

This work bears witness to the emergence of botany as a genuine scientific discipline, based on rigorous observation.

The illustrations contained in this herbarium are considered to be masterpieces of early-Renaissance botanical art. They represent whole plants in proportional diagrams, sketched with rare precision. Drawn from observation, defects and all, 238 marvellous woodcuts are compiled in this historic tome.

This work was one of thirty or so volumes donated to the Sélestat parish library by local clergyman Johannes von Westhuss. This imposing manuscript weighs in at 10kg. The trout skin binding is protected by metal clasps and sculpted ironwork featuring fantastic beasts.

The upper section is fitted with a chain, so the book could be attached to a reading desk in order to thwart potential thieves.